Robots in the UK

A unique choice transformed the UK - we can do it again

Reading through predictions from the 60's and 70's of how new technology would be used is a quick lesson in how bad we are at predicting the future. In broad strokes the ideas that computers would be ubiquitous and helpful, transforming communication and information were of course right. However, so many details were wrong. Really, embarrassingly, hilariously wrong. We still don't have those flying cars.

So let's talk about robots.

Actually, before then, let's talk about the BBC Microcomputer. In 1979, ITV produced "The Mighty Micro" - a series documenting and predicting the upcoming microcomputer revolution. The core theme of the programme was that microprocessors would dramatically change the whole of society, and that unless Britain took drastic action to educate the public and embrace the new technology it would get left behind. Previously computing had been seen as the preserve of enormous clanking machines in corporate offices or an obscure hobby for nerds with soldering irons. In the six part series, Dr Christopher Evans challenged that view - and presented a vision of computing as being an affordable, transformative, democratising force for positive change. The question was whether we would seize the opportunity.

So successful was the series that questions were asked in Parliament: how could the UK address the challenge and threat of the microcomputer revolution? The BBC in turn launched the Computer Literacy Project, with the goal of teaching the public about the new technology. It was funded by the Government to produce the Microelectronics Report that was subsequently shared with all MPs. Crucially, the report established the principle that education was key.

It's worth noting that at the time home computers were not a thing in the UK. The primitive ZX80 was yet to arrive. The Apple II was an obscure American machine that cost the equivalent of around £10,000 in today's terms for a typical machine. The first spreadsheet software, VisiCalc had only just been released. Machines were incompatible, difficult to use and people were still figuring out what exactly they could even do. What seems obvious now was anything but. Computer literacy was not so much about teaching the public how to do standard tasks, as a collaborative exploration of what these alien machines might be used for.

In that spirit, the BBC decided to commission their own computer to be the basis for an education series. Take a moment to consider that extraordinary statement. The computer scene was so nascent that they were not proposing to rebrand an existing product, or even build something that was compatible with an established standard (though CP/M was considered). They committed to making a completely new, incompatible, ground up design just to teach people about computers. They weren't documenting the arrival of current technology so much as leading it - and their ambitious specification aimed to be at the cutting edge of what was possible.

The project was controversial. The BBC was meant to be impartial, yet it was working very closely with the Government and contributing to our Industrial strategy. It was also promoting a commercial product, and choosing winners in the early competitive landscape of computer manufacturers. Clive Sinclair never got over the snub for the ZX Spectrum. More serious was the allegation that the project was essentially allowing the Government to fund industry through the back door and directing public finances.

However, if there was fault it could probably be excused in the light of the success of the programme. The BBC Micro became ubiquitous in schools, and companies supporting it with software and hardware thrived. If this was Government Industrial strategy, it worked. Even whilst some schools regarded the BBC Micro with confusion and left machines unused, many embraced the opportunity to use a computer that was the equal of anything available at the time. A generation of coders was born, hundreds of small businesses started and Britain as a whole took computers as a chance to step into the future.

And a single, foresighted decision changed the world. To meet the BBC's requirement of compatibility with a wildly changing landscape Acorn designed a 'Tube Interface' into the machine, that allowed different microprocessors to be easily connected to the Micro. That Tube interface enabled Acorn to experiment with it's own chips in an attempt to keep up with the rapid advances in technology. In 1985 - forty years ago - the ARM Microprocessor was launched. An estimated three hundred billion ARM chips have been shipped since then. That early decision to embrace the microchip ultimately led to the mobile phone we all carry with us everyday.

Right now, there's a new revolution starting. Two separate technologies are reaching maturity near simultaneously, and the effect is likely to be as profound - and unpredictable - as the microprocessor.

The first of those is AI - or more accurately machine learning. Whilst there are a lot of tentative, crystal-ball gazing suggestions of how AI will affect all of us in some future application, the real world ability to handle messy, human-scale information and sensor data is already proving transformative. The second technology is the hardware of robotics - in particular the sensors and actuators that allow us to build robust, accurate, cost-effective machines that can interact with our shared environment. Put together, these allow us to build robots that can walk, run, drive and fly, that can take instructions and solve problems, that can lift, carry and manipulate the world around them and that can perform useful tasks for operators that do not need to be highly skilled engineers.

In short, the robots aren't coming. They're already here.

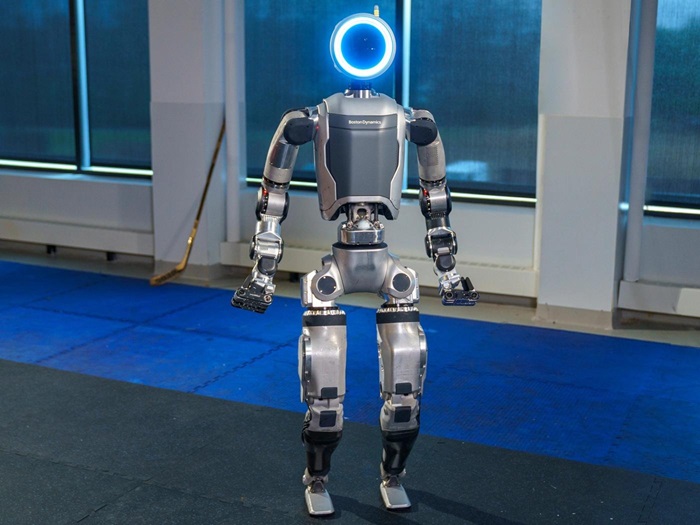

From Unitree's B2-W wheeled quadruped through to Boston Dynamics’ humanoid Atlas and truly self driving cars, we are seeing machines entering our workplaces, streets and homes. The ability to do useful work as well as entertain has exploded, and with it we're exploring new forms, new interactions and new ideas for how robots will be part of our everyday lives.

In short, we are now where we were in 1979. We don't know what the future will look like, but we can be certain it's going to be transformed. We don't know who the "winners and losers" will be, or how much our jobs and lives will change, but it's clear that change is going to be rapid, unpredictable and profound. We can also be sure that unless we embrace and understand this new technology and actively experiment and learn how we might use it, we will be left behind.

And just as in 1979, there is a powerful argument for putting robots - full sized, capable, advanced robots - in schools in the UK. As platforms for teaching science and technology, for learning about computers and AI, robots offer many exciting and engaging opportunities. We can also expect that the new wave of functional, useful machines will find other uses in schools that we can't predict - from running errands to supporting students - and we as teachers and parents can learn from those new experiences. If robots are going to become part of the fabric of our economy and society, we can benefit from educating ourselves at the earliest possible opportunity.

To underscore how fast things are moving, just a couple of years ago Boston Dynamics' revolutionary Spot 'robot dog' was launched at a price of tens of thousands of dollars - the Apple II of robotics perhaps? Yet recently Unitree launched a competitor in this space - the Go 2 which now costs under two thousand dollars. By sheer coincidence, its price matches the launch price of the BBC Micro computer almost exactly (adjusted for inflation).

Introducing robots to schools is not only a chance to hit that same vital tipping point, but also unlocks the same important second benefit - launching and turbo-charging our own industrial strategy. A domestic market for robots would be a welcome boost for businesses, researchers and investors in the early stages of this new industry. We should not merely encourage, but demand that UK based companies are core to supplying machines, software, educational materials and support for schools. We should be manufacturing our own robots. At present we have many of the skills and capabilities, scattered across the high-tech automotive and aeronautic sectors, electronics design and fabrication companies, software developers, researchers and educators - but have not had the 'grain of sand' around which pearls can form. Overseas companies are stealing the march - and our talent - to get there first. Unless we act decisively and fast, we will be left behind and unable to catch up.

We can imagine a world where the BBC Micro did not exist. Where tens of thousands of leading software engineers and technologists did not get the opportunity to geek-out at school over a machine that seemed like the future. Where global companies were not grown out of classrooms and kitchen-table businesses. Where those expensive American machines were permanently just beyond our budget. Where patient TV presenters didn't explain what ordinary people could do with an alien technology during evening broadcasts. Where we just impartially observed, rather than acting to change the future ourselves. It would have been a huge loss, a failure of imagination and commitment.

So right now we need to ask ourselves if we want to make a new and brave commitment, or let opportunity slide away just as other countries are seizing it and transforming their worlds. If the robots are coming (and they are), we should make sure it is on our terms, to our benefit and for our children.

- Andy Toone

Back to My Writings