Dynamicland: An Introduction

Bret Victor wants us to see data differently

Humans, on the whole, aren’t very good at reasoning about abstract, big ideas. From climate change to viral spreads, we struggle with concepts such as comparative scale, change over time, probability and risk. This is one of Bret Victor’s key insights and drives his current ambitious project, Dynamicland.

Dynamicland itself defies categorisation. It is at once a public forum, collaborative experience, physical space, user interface and computational resource. It’s aim is to teach, share knowledge and to provide a tool to reason about subjects that we find hard to conceptualise. This is a brief introduction to Victor’s work, and some observations on his experiments and solutions.

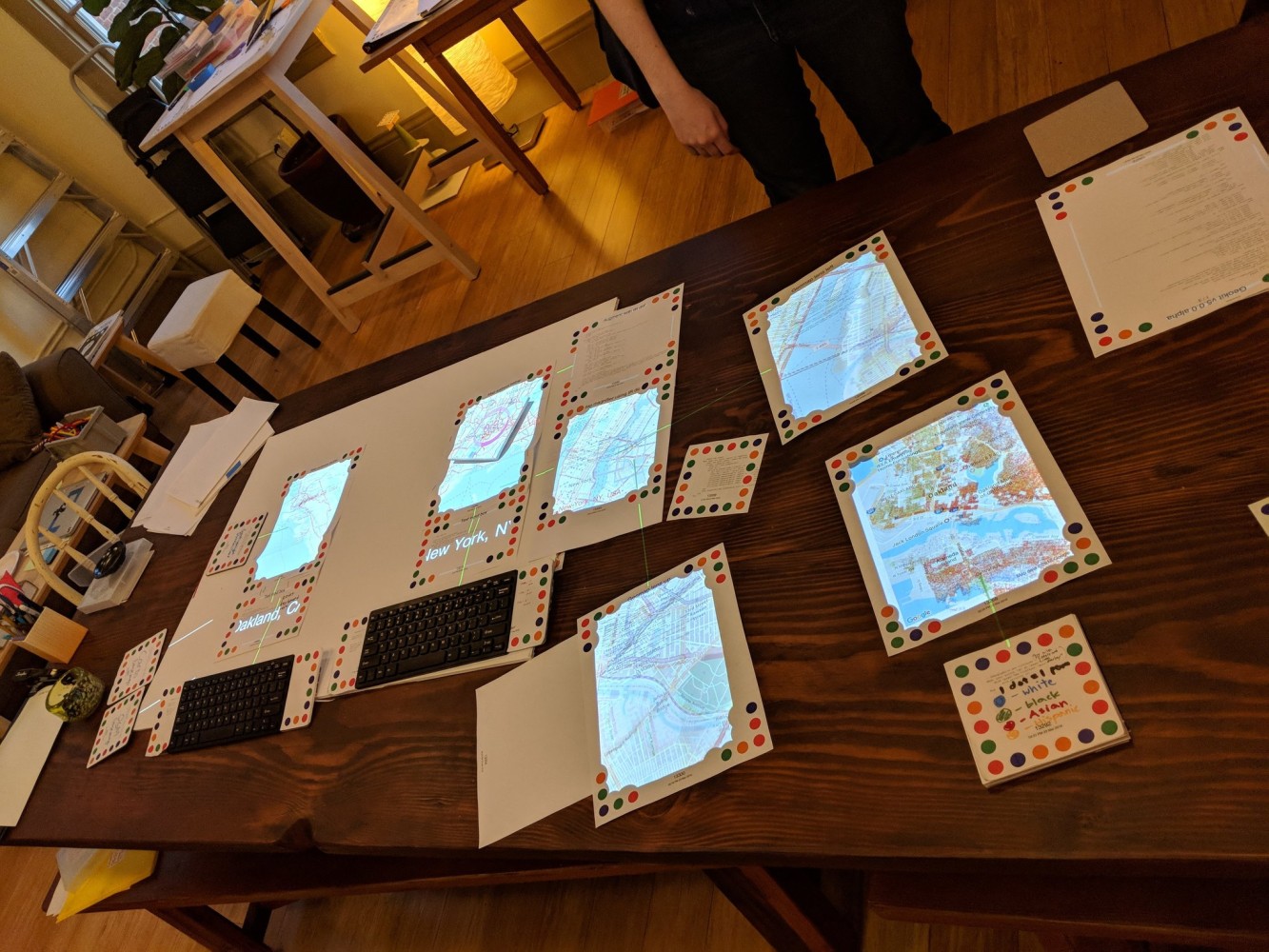

To experience Dynamicland you need to head to Oakland, California. There you can walk into a space arranged like a craft workshop. Large tables are surrounded by people and covered with casually arranged pieces of paper and card. The pieces have colourful dots placed at their edges. Some are glowing with text, charts and maps projected down from the ceiling. Animated images leap from page to page. When they are rearranged, the images respond and change. This is the first ‘artifact’ of Dynamicland: physical objects that communicate and interact.

The concepts flow from here. Humans are well tuned to think about the physical world, to use relationships like “next to”, “before”, “after”, “on top of”. We learn to reason through play and experimentation. We use things to represent concepts — this is a map, a chart, a piece of information. We share understanding by collaborative experience. Dynamicland embraces all of this by taking disembodied, isolated information away from our computer screens and putting it into a shared space where we can explore relationships and concepts physically. There is a superficial resemblance to children learning in kindergarten: What happens if I put this here, or adjust that? We forget how effective this sort of learning is.

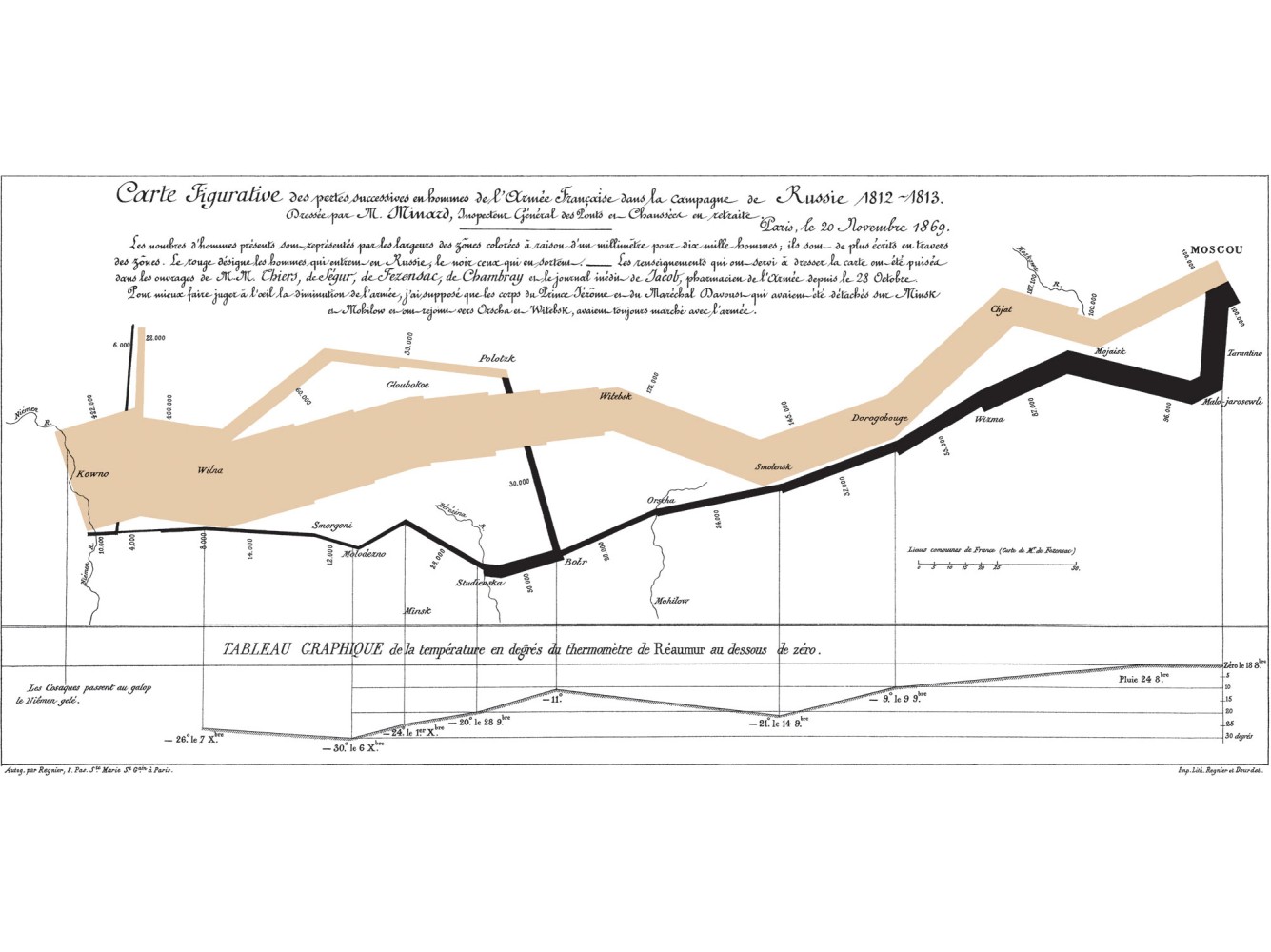

For Victor, this is also about media. His research highlights the leaps in understanding that followed the invention of maps and modern numeric charts. By finding new techniques to represent information, we improve the ways we can reason about the world around us. One such example is the first ‘infographic’ — a chart produced in 1869 by Charles Joseph Minard showing Napoleon’s shrinking armies as he disastrously attempted to invade Russia in 1812.

Famously described as “the best statistical graph ever drawn”, Minard’s chart introduced visualisation techniques routinely used today. By conveying data in new ways, we are better able to interpret and reason about it. Relationships, scale, change and consequence can be visualised and shared. With Dynamicland, Victor asks how modern media — the interactive environment our computers enable — can advance our understanding even further.

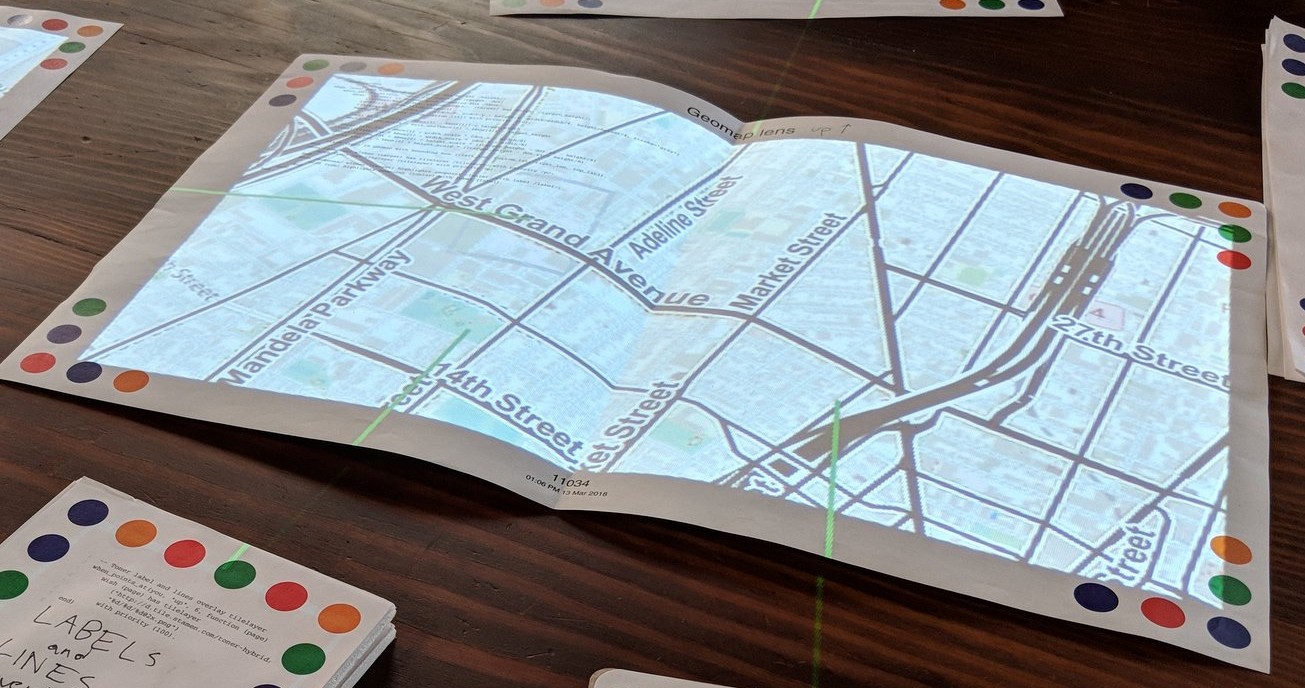

The answer it presents is to think of the user interface typically provided by most computers not as a facsimile of traditional media, a delivery mechanism for static charts and maps, but as a tool to simulate the world around us. Rather than passively consume a representation of data, we should be able to grasp a model and adjust parameters, rewind time and ask “what if?” questions. Documents like the one you are reading right now can at best show a snapshot of an idea. Dynamicland offers an environment where every chart or diagram is backed by a simulation, and invites the user to explore how it behaves.

In practise this means that simple concepts can be explored through play. Draw out a waveform on a piece of paper, and hear what it sounds like. Attach a filter, simply by placing it next to the waveform and hear, and see the change to the waveform. Put a dial next to the filter and adjust it’s parameters instantly. Physical objects representing abstract concepts, backed by simulation and enabling exploration.

It also means that far more complex ideas can be communicated. Attach a model of viral spread to a map and see how it passes through the population. Link it to a chart and break out infection rates in demographic groups. Add representations of possible responses to the model and explore how they might change the course of the virus. One of the challenges during the Covid pandemic has been to share and understand the risks and uncertainties faced by our medical community, and the consequences of political and health decisions being offered. Somewhat presciently, Dynamicland suggests that an environment where these ideas can be explored in depth improves both understanding and debate.

Here, Victor turns to the examples of Nasa and the Fermilabs for inspiration.

He argues that when we are dealing with complex systems and behaviours, we have learned to build not just individual tools to interact with them, but environments that place all of those tools to hand. A physical workspace might arrange tools to construct, shape and build complex devices. What Victor terms “seeing spaces” allow us to arrange different perspectives, controls and insights in a way that provides instinctive access to abstract concepts and information. Dynamicland attempts to bring individual tools out of the confines of our screens and integrate them seamlessly into a consistent environment.

In practise, Dynamicland turns a room into a computer (with an operating system, Realtalk) where people can work together on data and interactive models. Paper and card in the room become responsive, ‘smart’ objects. Small snippets of code printed on a page add behaviour so that when it is placed down it might show a particular item of information, or act as a control. Projectors and cameras mounted in the ceiling, track where everything is and turn any surface into a view into the system being explored.

This way, a sheet of paper becomes an interactive map, showing changes in real time as other parts of the model are adjusted.

Demonstrations show this “seeing space” being used to teach science to children, create strange musical instruments, learn programming and explore government information and history. This is unashamedly ad-hoc, with each experiment playing with different ideas and tools. The inner workings are openly exposed. The code that runs Dynamicland is on each page in various mutations, and spread across the walls to be altered and updated. The experience of being inside the computer is reinforced and each demonstration is as much about building the demonstration as understanding the information it imparts.

Here, the impression is that Dynamicland is very much a child of the pioneering experimentation of Xerox’s famous Palo Alto labs. This is perhaps no coincidence as Victor is a protege of Alan Kay, the developer of Smalltalk at Xerox. Xerox explored unique new ways of interacting with computers years ahead of their time, with the Smalltalk GUI introducing key concepts such as the desktop user interface. Similarly Victor presents a far future timeline for Dynamicland, envisaging his seeing spaces evolving into a public resource, a “new form of library” provided by communities to their members. Ultimately he imagines it becoming a pervasive medium, built into every environment so all objects can share knowledge and empower people.

The vision is studiously non-commercial. This too reflects the Palo Alto ethos — it took Steve Jobs to see the work Xerox was doing and to build it into the successful and hugely influential Apple Mac user interface. Dynamicland eschews such corporate concerns. It is a non-profit organisation, and Victor’s long timeline is designed to allow for iterative and experimental research towards his distant goal decades hence.

Unfortunately, this limits the utility of Dynamicland today. The only way to access it is to visit Oakland, where Victor curates spaces demonstrating the possibilities. The apparatus and code that runs Dynamicland is not publicly available. The demonstrations are persuasive, but the space itself appears prototypical, raw. Just as Xerox derided Apple for creating a pale imitation of it’s grand vision, Victor appears determined that Dynamicland must be experienced in its entirety and no less.

Yet the concepts brought together in this experimental space offer us some exciting possibilities that we can explore today. Where Dynamicland has its eyes on the distant future, we can consider what immediate utility we can start building now.

We can ask how we can expose existing sources of data and simulation so that they can be visualised and combined in an intuitive and trustworthy manner. This remains a perennial problem of public bodies attempting to gain insight and maximum value from the vast collections of information they oversee.

We can consider the value of “models as information”, where we can replace static data with computer models that can be reasoned about, compared and validated. By providing models rather than data, we can ‘compress’ concepts into a form that we find naturally easier to understand — learning through exploration and play. This contributes to the many social issues we face today that remain stubbornly hard to intuit from static and partisan collections of data.

We can begin to build pervasive information environments, where augmented reality encourages physical collaboration. Not only does this break away from the isolation of screens, it encourages knowledge sharing through exploration. Here there are opportunities to replicate Apple’s success in taking the raw, unbounded possibilities of Smalltalk to produce a more semantically bounded but immediately useful tool. As with Apple, democratising the tool itself, making it accessible to many users could dramatically accelerate its evolution.

Dynamicland therefore offers us a glimpse not only of the future, but also the huge power in reimagining our existing interfaces with computers. In bringing together the strands of interface, simulation, collaboration, knowledge sharing and physical presence, Brett Victor encourages us to think about the assumptions we build into our current tools. As we are faced with ever larger collections of data and information every day, Dynamicland shows that the tools we use to consume them play a key role in enabling us to make sense of the world around us.

Further links:

- Dynamicland: https://dynamicland.org/

- Media for Thinking the Unthinkable: https://youtu.be/oUaOucZRlmE

- Hackster.io Visits Dynamicland: https://youtu.be/OQpr454yhvM

- Bret Victor: Seeing Spaces: https://youtu.be/klTjiXjqHrQ

- Charles Joseph Minard: https://ageofrevolution.org/200-object/flow-map-of-napoleons-invasion-of-russia

- Andy Toone

Back to My Writings